An exploration of the challenges and expectations of operating a small business in Jackson Heights amid demographic change, drawn from interviews with small business owners specializing in products ranging from cultural items to general neighborhood services. Note: Fieldwork for this study was undertaken before the Covid-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020 and the subsequent lockdown. ︎ Abstract and full paper here.

INTRODUCTION

New York City has a long tradition of small business, from the earliest pushcarts and markets to today’s street vendors and shops. Some of the most recognizable, like the much-beloved bodega, were first established by immigrant communities in response to a demand for specialty products and, often, informal social spaces. Today, 48 percent of New York City’s small businesses are immigrant-owned, employing half a million New Yorkers and contributing billions of dollars to the city’s GDP.

In the 1950s, Colombian and Cuban entrepreneurs began to establish businesses in Jackson Heights, Queens, contributing to the formation of some of the first immigrant communities in the neighborhood. Three decades later, the first Indian-owned businesses in Jackson Heights opened as Indian entrepreneurs began leasing vacant storefronts. Retail clusters like these have been called "ethnic enclaves", broadly defined as places with high concentrations of businesses and customers who share a common ethnic identity. Today, businesses in Jackson Heights’ “Little Colombia” and “Little India” are more accurately multiethnic. Globalization and economic mobility have brought about a neighborhood that is increasingly diverse in every sense of the word, transforming the commercial signature of the place. How a neighborhood’s small businesses interact in this space will help shape the future of its retail corridor.

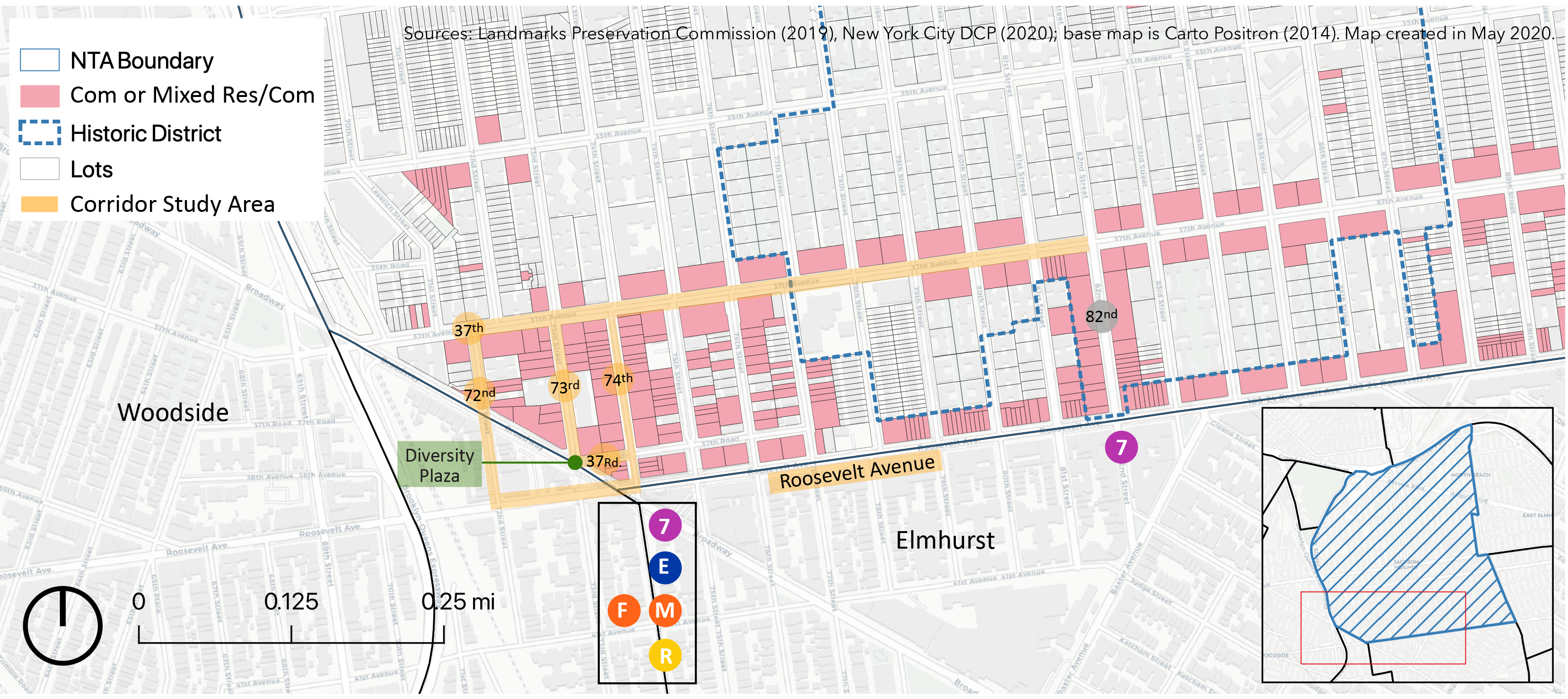

Twenty-two small business owners in Jackson Heights were interviewed for this study, which compares the experiences of businesses on or near 74th Street that were originally conceived to meet the needs of the South Asian community through the offering of specific products and services (12) to those of general businesses like pharmacies and hardware stores, primarily on 37th Avenue (10). They deal in products ranging from saris to prescription eyeglasses and self-identified as coming from a variety of backgrounds. Despite their varied offerings, contrasting priorities, and different personal journeys, business owners experienced similar dynamics buoyed by a reliable customer base and long-established corridor, as well as both anxieties and hopes regarding ongoing demographic changes.

FINDINGS

I. Transnationalism

The market for buying gifts to send or take back to one’s homeland was prominent in the early years of Jackson Heights’ South Asian enclave. In the 1990s, the retail block on 74th Street had several electronics shops that sold imported 220V appliances, which were a popular gift to bring back. Area businesses have since slotted themselves into different roles in the local economy, from international money transfer services that advertise currency exchange rates to luggage sales that complement purchases bound for abroad. Forty years on, the 74th Street retail strip has not only endured but grown, though its core customers may have changed. Business owners noted subtleties in customer preferences, such as vegetarian food preferences among some groups, halal among others. Groceries and supermarkets seem well situated to accommodate and adjust. Meanwhile, among general neighborhood businesses there was an acknowledgement of the need for multilingual customer service.︎︎︎ Use the left/right arrows to browse interview quotes:

II. The Location + Reputation Advantage

Cultivating a reputation by word-of-mouth was the modus operandi of businesses old and new. Some of the business owners contribute to community causes that grow their reputations in lieu of resources dedicated to conventional marketing strategies, though the societal pressure to contribute financially can also feel burdensome. Ultimately, the business owners valued the trust built up over years of service to their community. This may however be a source of anxiety in markets where business is slowing. For purveyors of South Asian clothing and jewelry, for example, the reputation advantage is upended by nature of new customers’ unfamiliarity with the market and products.Walkability and the absence of big box enable businesses to occupy spaces and provide services for which people would otherwise go to a big retailer. Jackson Heights’ co-ops in particular have helped 37th Avenue establish an ecosystem of its own. Five of the nine businesses interviewed along 37th Ave referenced the co-ops as helping to add to the homeowner population, and thus, residents who would be in the community for some time—“embedded” as one business owner described it. And there are long-time relationships embedded in the long-time businesses. During one interview, a customer shared, “That’s why you come here and you don’t go to Home Depot... because you get personal service. However many times I’ve moved, I [come here].” The owner responded, “See, that’s the service I’m talking about. No matter what, they [big box] can’t take that away from us.”

︎︎︎ Use the left/right arrows to browse interview quotes:

[ Findings/II continued ]

Few people used the term “gentrification” specifically, but they alluded to common anecdotes, such as a “Manhattan crowd” moving into the neighborhood. The effects were perceived to be concentrated around the upper 70s to 80s; one business owner near 74th Street declared that his location was “not attractive to white people.” Another business owner observed that “the 80s” had new storefronts with “a different look, maybe a more gentrified look” as well as a Starbucks, the presence of which is popularly perceived as a telltale sign of neighborhood change. “The only thing constant is the change,” he added.

III. Community Cohesion

“Community” was invoked in different contexts: the hyperlocal business community, the co-op community, different ethnic communities. Jackson Heights organizations plan cultural events and the neighborhood hosts two annual neighborhood-wide parades for Queens Pride and Halloween. However, there appears to be no mechanism for interaction between retail blocks, with each section of the corridor operating independently. Although there are many advantages to a long-established business corridor, some business owners sensed that the business community is entrenched in a way that has not come to terms with today’s needs. Few credited local merchant groups with much beyond asking for donations and offering advertisement opportunities (and “not digital” advertisements, pointed out one business owner, who said that the association he was acquainted with skewed older and was “old school” when it came to marketing).Others credited the local merchant groups in discussions about organizing street fairs, addressing parking needs, and supporting City efforts to convert an intersection near Roosevelt Ave into a pedestrian plaza. Only three immigrant business owners mentioned engaging with local political bodies. Though people were aware that avenues of access to resources were available, few took part themselves. The time-consuming work of running a business, an aversion to politics, or language barriers precluded it in some cases.

︎︎︎ Use the left/right arrows to browse interview quotes:

IV. Modernizing + Adapting

“If I can convince you,” said a jeweler, “you won’t shop around to Tiffany’s. You will buy from me. But you should be able to trust me, and to gain that trust, I should be able to convince you.” This was a common refrain among the business owners, who shared two perspectives on modernization:1. Elevate the reputation of the corridor, both to position the corridor as a prime destination for retail and attract young people to spend and invest in the neighborhood.

2. Establish an environment where businesses can more adeptly, and with less risk, respond to the current needs of neighborhood residents.

For business owners who experienced 74th Street’s evolution into a main retail destination for products from the Indian subcontinent, in recent years there has been a conspicuous reduction in traffic. Now there exist other hubs for people to buy such goods, “unless you want to buy a lot of stuff for a wedding or something, then you come to Jackson Heights.” As the second and third generations come of age and possesses disposable income, business owners see an opportunity to encourage community interaction with a quality shopping experience and enable “Insta-sharing of food” by people who seek an experiential outing. Merchants compared themselves and their peers to national and international brands in an aspirational way—to position their small businesses with the same attention to brand and customer experience, “So even though this is Jackson Heights, this can be downtown Manhattan.”

︎︎︎ Use the left/right arrows to browse interview quotes:

But Manhattan was also invoked in the context of rent and other costs. At the time of interview, a grocery and butcher shop was gearing to close after nearly 30 years. The owner noted that though competitors started to enter in the late 1990s, competition “skyrocketed” around 2006. Ultimately, for his business the reputation built from being one of the first Bangladeshi businesses in the area came up against hard accounting. He and another business owner who cited the crowded retail market decided to leave retail entirely in pursuit of service-based businesses.

An environment in which entrepreneurs can take risks has the potential to attract younger business owners with new ideas to the corridor and stimulate investment into the community. But according to business owners, in the 74th Street block the old guard is entrenched; in other parts of the neighborhood, like along 37th Avenue, amenities like childcare lag behind the community’s needs. Two business owners on opposite sides of the age spectrum also observed a lack of new young entrepreneurs in cultural businesses. For immigrants, entrepreneurship can be a path to economic mobility. “They came here to establish themselves,” said the older member, “and that is how they’re using it. And after they learn something, they’re flying away." “Everyone is a programmer,” said a second-generation business owner.

CONCLUSION

“Sometimes I call it blood money,” said a business owner who has been in the neighborhood for 32 years, “because I work all holidays. I don’t know what Easter or Christmas are like.” In every small business success story, there is the reality of grueling hours, complex regulations, and the daily arithmetic of sales against ever-growing expenses. Sometimes the challenge comes from certain external forces—unreasonable rents, lease disputes, or permit issues. Other times, the challenges are a function of a business’s life cycle, as when a successor to the business is not found, or the market changes irrevocably. Those non-market forces were the focus of this study.The business owners interviewed were not interested in preserving the corridor in its current state but, rather, conserving its foundation—shops of cultural significance and small businesses that provide personal attention. The area’s affordability is what made it the neighborhood it is today. In that distinction, it has fostered an environment in which skill-sharing and success enable entrepreneurship. For small businesses to modernize, compete amid e-commerce and chains, and continue to contribute to the local economy and invest in the local community, they will require the tools and the space to do so. Communities are not static; they form, shrink, and shift as homeownership, wealth, and generations grow. As some groups mature and resettle beyond the neighborhood, newer communities can establish their place in the corridor, building on the investment of their predecessors. An organized approach to capacity building and corridor-wide planning in the neighborhood, paired with a commitment to the types of affordability that enable small businesses to thrive, will be essential to the corridor’s longevity.

Q1: What drew you to Jackson Heights for business?

Q2: What are your expectations for the corridor?

Use the buttons below to filter responses. Place cursor on a card to flip ︎︎︎ to the other side for more comments.

The neighborhood was Desi-oriented. There were Indians and Punjabis. It wasn’t clear that it would become Bangladeshi, but it was similar.

As for why entrepreneurship among the younger generation has lagged, the business owner, himself second-generation, posited that “people are scared to do it because it is risky. There’s still an old-fashioned mentality. And entrepreneurial interest among Desi-Americans is dying.”

I knew there was lots of community-based [business] but is my community enough to support my expenses, you know? Will I be able to do enough business where my expenses will be met? But once I opened the business it proved that yes, there is.

“I guess we still have to improve,” he said, “The ambience of this business is not right for sure.” He questioned the dissonance of paying such high rents yet having to request police officers to monitor the area because of thefts. He was also worried about losing customers because they had one bad experience in Jackson Heights. “Within my merchant group, they should understand how to deal with people.”

I picked Jackson Heights mostly because we found a significant overlap in customer base… And it was close enough to our [other] store that we could move and transfer products. I also know some people who have businesses in the area.

On future outlook:

City Council has a lot [of the responsibility] when it comes to regulation about storefronts. If we can’t afford it, we will leave. [But] I would double the size for my store tomorrow. I think it’s a very strong community.

The family had worked/operated in the neighborhood for a long time so they knew the people and the area well.

On the future of the corridor:

It’ll get bigger and better... There are a lot of community groups and Jackson Heights Beautification Group has been cleaning and planting. ... Online business is hard not just for us but for everyone. ... A lot of young people come in. A lot of co-ops or rental apartments attract people who will live here for a long time.

When we came into this country my father’s family friend was in the electronics business. He told my father to come in so they started working together... That person was based in Jackson Heights so that’s why. When you learn, you learn with the same community and everything.

When I took over [in 2001] it was more Indian and Pakistani. It’s funny because people still think of Jackson Heights as Indian but it’s really not anymore. Maybe at that time. Probably before that, too, a Spanish influx, [now] Tibetan. And in the last several years, white people moved back in too so it’s more mixed... We all had English. [For Bengali customers] we tried getting a salesperson who spoke the language… It makes a difference.

We zeroed in on Jackson Heights because it was close to our homes, there was foot traffic, it was well-established, and there used to be a [similar business] here.

On the evolution of the corridor:

If you’re able to provide to everybody, you have a good chance of succeeding. It’s not guaranteed, but it’s a chance at survival... The older you get, the more you want to stabilize the community you live in.

People from other states know that there is an Asian market for gold jewelry in Jackson Heights. There are more than 30 jewelry stores throughout, including small ones.

In the last few years, Jackson Heights has changed a lot. There were few jewelry stores before. There are more choices now. The Desi community is also big. The Bengali community has been the majority in the last eight years. Once people get into the neighborhood, they don’t move. And groceries are cheaper here than in other places. It supports the community.

It was the only Desi community for shopping [in the 1990s].

Another merchant with a similar business observed that with today’s multicultural ties, people of different backgrounds come to shop for Indian weddings. But there was also pessimism about the future: "I don’t see the customers that used to come from Long Island or NJ. ... There’s no future here. People only come for the old gold stores. Property taxes go up and owners raise rents. How can we convince the landlords?"

People in this community—a lot of Indian, Bangladeshi, South Asian people—they like to send gifts to their family. Many people staying here alone, family not here.

“I don’t think they’re doing something better in actual policy, actual actions... They have some organization, but it’s like a signboard,” he said about a local business association. He worried about the economic outlook for his main customers, lower-income, lower-skilled workers.

The [Bangladeshi] community was small at the time and there was no business like this here.

The business has since pivoted to selling and repairing electronics, and now sees a greater variety of customers. It was necessary and inevitable for the business’s survival; a “community-based business” alone, he believed, would not work anymore. Another employee added, "House rent is also high, so how can people live here? Who is affordable housing serving? How is an income of $50,000 affordable?"

You have all these buildings with a lot of apartments. And at the time it was a lot of rentals so there was constant movement—people moving in, people moving out. So it was the perfect neighborhood for it.

There’s nothing in the neighborhood. People usually have to go to Home Depot or outside in Long Island.

Jackson Heights is one of the first neighborhoods in NYC that built co-ops, way back. And that, more than anything, is probably what helped me stay in business and get me going. Word of mouth. Oh, who did that? And so on, and so on.